The RIAA just won’t quit. They’re taken up the crusade to push for anti-piracy legislation once again, as seen in this New York Times Op-Ed piece titled “What Wikipedia Won’t Tell You” written by Cary H. Sherman,chief executive of the Recording Industry Association of America, which represents music labels. The content of the piece is incendiary, and that’s being kind. The RIAA is adamant about their stance on piracy and are pressing the issue in every outlet they can. To quote Digital Underground from their Sons of the P album — which currently is not available for legal purchase online due to holes in the DU library in various legit digital music resources — “Like Ice Cube says, Once Again it’s On.”

Everyday They’re Shufflin’

The Stop Online Piracy Act and the Protect Intellectual Property Act were both killed in Congress — shelved because they were too wide open to abuse. The protest against these bills reached a collective crescendo when internet giants Wikipedia and Google and WordPress teamed up with a host of others for an internet blackout. When the largest source of internet information — and grade school kids’ favorite spot for help with their homework — goes dark and the search engine juggernaut that fuels the internet shines its spotlight on your bill, things have finally gotten serious. The U.S. citizens took notice of this blackout, and joined the internet in protest. And Congress heard the people and backed off this poorly written legislation.

But that hasn’t stopped the entertainment lobby. They went back to the drawing board and then returned mere weeks later with a new idea on how to combat online piracy. Unfortunately that new idea was the exact same idea as before. This was seen in the wishlist the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) released. The highlights of this list are essentially that the music industry wants pretty much the exact same things that were in SOPA, the same things that prompted the protest in the first place. A list of seven demands, which include the exact same far reaching calls for search engines and payment processors to police websites individually and be responsible to law enforcement for content they are indirectly connected to.

We’ll get back to this, but for now the point is the music industry felt the need to push for the same stuff that killed SOPA and PIPA. And that came right back to the forefront with Mr. Sherman’s opinion article in the New York Times. Essentially the RIAA wants a do-over and Mr. Sherman is here to tell us why that needs to happen.

Come At Me Bro

So today The Official Merchant Services Blog is going to try to put this issue in its place much like Blake Griffin did to Kendrick Perkins recently. Yes, we are going to Posterize the RIAA. Because the op-ed article indicates the RIAA has soft interior defense and can’t play man to man very well at all. First up we’ll start with the relative hypocrisy of Sherman’s ill-timed article found in this contextual relationship: Suggesting Wikipedia isn’t telling people everything, and then making this comment, “They knew that music sales in the United States are less than half of what they were in 1999, when the file-sharing site Napster emerged, and that direct employment in the industry had fallen by more than half since then, to less than 10,000.”

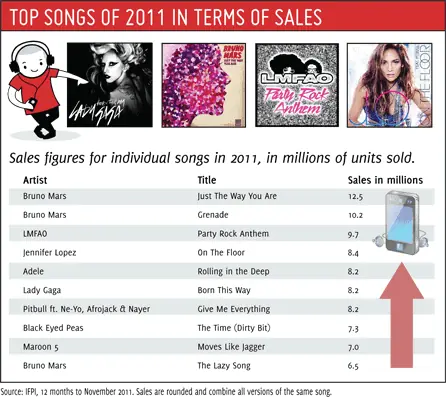

This is hypocritical because Mr. Sherman is leaving out some very pertinent information — which his employees were just recently bragging about on twitter. As we reported on January 31, the RIAA was excited about the IFPI wishlist because it had a series of statistics that showed the music industry is doing well with digital sales. The music industry claims Wikipedia is being deceptive and then suggests that they are still reeling from Napster, which was effectively scuttled back in 2002. They’re making a play for sympathy from an issue that happened almost a full decade ago, and yet they just got finished gloating about how successful they were this year!

Jonathan Lamy, senior VP of Communications for the RIAA, tweeted that paid subscription services rose 65 percent to 13.4 million in 2011. This tweet was in response to figures released by the IFPI which Lamy was excited to read. Lamy also tweeted that paid digital music services are active in 58 countries, generating $5.2 billion in revenues.

And then Cara Duckworth. The VP of Communications for the RIAA also cited the IFPI figures and then said: “W/more than half of all music sales coming from digital services, we know how Internet works. “Music=Innovation. Declare THAT. #CES #SOPA.”

What the RIAA isn’t telling you is far worse than what Wikipedia isn’t telling you. But Mr. Sherman isn’t about to concede facts when the agenda needs to continue to be pushed. The music industry is finally getting the hang of the digital market. Their own people brag that they know how the internet works. Declare that! But Sherman’s still waving the Napster suit in your face trying to claim that Wikipedia is obfuscating the issue.

It gets worse.

Born This Way

Sherman writes, “While no legislation is perfect, the Protect Intellectual Property Act (or PIPA) was carefully devised, with nearly unanimous bipartisan support in the Senate, and its House counterpart, the Stop Online Piracy Act (or SOPA), was based on existing statutes and Supreme Court precedents.”

The only thing in that statement that is rooted in the reality of what happened with SOPA and PIPA is that there was a lot of bipartisan work. Unfortunately, the work was bipartisan unity on finding problems with the so-called carefully devised legislation. Tech industry experts on both sides of party lines found the problems and holes in the legislation. As we reported on December 27, 2011, SOPA sparked unity in the federal government. And as we’ve written in our in-depth analysis, the bill was not very carefully devised at all. In that analysis we lean heavily on discussion from Congresswoman Zoe Lofgren [D-CA], an expert in the tech industry. We’ll highlight just a bit of Lofgren’s criticism of this bill, with questions raised: “Section 103 also allows a “portion of” a website to be deemed “dedicated to the theft of U.S. property,” regardless of the culpability of the website as a whole. Like many important terms throughout H.R. 3261, the precise meaning of these words is ambiguous, and will require years of expensive litigation to clarify. However, the plain meaning of the words seems to indicate that any large website could face a risk of termination by payment and advertising providers based solely upon infringing material contained in a single web page. ”

This is not carefully devised legislation. And as we eventually reported, the bill’s own sponsor admitted he did not fully understand the technical aspect of the bill and he backed off of it. Bill sponsor Lamar Smith is quoted in various media sources as saying: “I have heard from the critics and I take seriously their concerns regarding proposed legislation to address the problem of online piracy. It is clear that we need to revisit the approach on how best to address the problem of foreign thieves that steal and sell American inventions and products.”

To Be Continued